Commentary & Essays

‘Zine: Fascism & Anti-Fascism: A Decolonial Perspective

Published

8 years agoon

By

Rudy

By Ena͞emaehkiw Wākecānāpaew Kesīqnaeh

Originally published February 11, 2017 at www.onkwehonwerising.wordpress.com/2017/02/11/fascism-anti-fascism-a-decolonial-perspective/

Downloadable ‘zine format here. (PDF, 425kb)

Truly, there are stains that it is beyond the power of man to wipe out and that can never be fully expiated.

But let us speak about the colonized.

I see clearly what colonization has destroyed: the wonderful Indian civilizations—and neither Deterding nor Royal Dutch nor Standard Oil will ever console me for the Aztecs and the Incas.

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism

In the wake of the election of Donald Trump to the south of the colonial border, there’s been a blooming of discussion on fascism and the necessity for anti-fascist organizing amongst various left-wing streams of thought (anarchists, Marxists, anti-racists etc.). This has only increased in the wake of his inauguration, the subsequent series of worrying (though unsurprising) executive orders that he has issued since taking the office, and the resistance that has flourished against them.

Whether or not Trump himself is a fascist is a question that’s up for debate (many who argue that he is no doubt point to claims by one of his ex-spouses that he sleeps/slept with a volume of Hitler’s speeches next to his bed). It is also arguable that several key political figures within his inner circle, such as Steve Bannon, are para-fascist. Undeniable though is that Trump and his closest advisers are right-wing national-populists, which in the context of north amerikan settler colonialism is, invariably, inseparable from white nationalism.

Likewise, it is undeniable that a number of explicitly white nationalist organizations have been highly motivated and emboldened by Trump and his broad popular support amongst amerikan settlers, across gender and class lines, who perceive amerika as having been betrayed and dirtied by immigrants, “minorities,” queers, feminists and a neoliberal capitalism that has sent industrial jobs overseas. Driven by these broad feelings of white ressentiment, and thirsting for a new frontier, these prophets of naked and proud white power, such as Richard Spencer, rallied to Trump’s campaign, and now presidency. Whether they will continue to stay in Trump’s corner though is yet to be seen.

Additionally, as I write this from kanada it would be foolhardy to believe that this country is hermetically sealed from what has been going on south of the border. Prominent figures in the race to replace Stephen Harper as the leader of the federal Conservative Party have sought to emulate Trump’s rhetoric, and have even openly called for bringing his message here. Do not forget that before Trump’s executive orders barring immigration from seven Muslim majority countries and authorizing the building of a wall on Mexican border, the late Harper administration passed the nakedly Islamophobic Zero Tolerance for Barbaric Cultural Practices Act, as well as the Anti-terrorism Act, 2015 (Bill C-51) and the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (Bill C-24), two laws which have respectively strengthened the already existing kanadian police state and allowed for the stripping of kanadian citizenship from dual citizens and those with the ability to obtain dual citizenship. None of these are issues that been positively acted upon by the current Liberal Party government of Justin Trudeau.

Most strikingly, and tragically, of course, is the recent shooting at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City. This event, which cost six lives, was carried out by a French-speaking settler who openly espoused support for the right-wing national-populism and Islamophobic politics of Trump as well as Marine Le Pen in France. Many fear that acts such as this could be the tip of the iceberg, rather than some sort of isolated long-wolf type incident.

In general, while the emergence of the north amerikan far-right goes back further than Trump, and was certainly emboldened by the election of Barack Obama as the first non-white person to the office of the president, Trump’s campaign and subsequent electoral victory has undeniably led to a marked acceleration of the movement. For the time being, naked white nationalists feel that they now have one of their own in the White(st) House, or, at the very least, someone who will lend them their ear when they come calling and who’s movement they can springboard off of in order to further build their own.

I also know and want to recognize, that many people are scared as well of the current situation. As I noted in my commentary on the Trump election, my mother called me at nearly 3 in the morning to tell me that she felt like she was going to throw up in light of. Similarly, my brother, who is generally no liberal, told me that he felt as though he may have to leave his job because of the smothering atmosphere of Trumpian white nationalism in his workplace. Since the election I’ve read what seems like daily updates of the fear, depression and rage felt by many of my fellow Indigenous scholars, and many, many non-scholars, as Trump has re-activated pipeline deals, ordered the construction of a border wall to keep out our Indigenous family from south of the Rio Grande, and hung a painting of perhaps amerika’s most prolific Indian killing president, Andrew Jackson, in the Oval Office. The fears and worries being experienced and expressed by family, friends, colleagues and comrades across Turtle Islaare is palpable, and it would be cold, as well as disingenuous, for me to not give space and voice to those feelings.

Bracketing off some of these issues though, what I want to do here is to ask a basic question: what is fascism? And, more particular to what I want to say here, what does fascism mean to Indigenous people? Is it even a useful analytic category for us in light of existent settler colonialism? Also, what does anti-fascism mean to us in light of the struggle for decolonization?

Defining Fascism

So what is fascism? Open any left-wing tome and you are bound to come across one of two definitions. The first, and perhaps more common these days, views fascism as some form of particularly virulent authoritarian nationalism. Generally they attach fascism to manifestations of aggressive racism, reactionary and conservative traditionalism, anti-liberalism and anti-communism, as well as expansionist and revanchist approaches to foreign policy as part of a general movement towards the seizure of absolute political power, the elimination of opposition and the creation of a regulated economic structure to transform social relations within a modern, self-determined culture. Other essential features include a political aesthetic of romantic symbolism, mass mobilization, a positive view of violence, and promotion of masculinity, youth and charismatic leadership (Griffin and Feldman, 2004). The general historical examples of fascism, without paying much heed to unevenness between them, are the Italy of Mussolini and his Fascist Party and, of course, the National Socialist movement that seized political control of Germany in the early 1930s. Additionally they may look to Franco’s Spain, the clerical fascism of Romania under the Iron Guard and Ion Antonescu, or the various governments of Hungary in the 1930s and during the second inter-imperialist world war.

To the left of this essentially liberal-historical, though not entirely unhelpful, definition of fascism is that which is taken up by the majority of the revolutionary anti-capitalist movement, primarily by Marxists, though also by class-struggle anarchists as well. This particular definition traces itself back to the Bulgarian communist and General Secretary of the Communist International Georgi Dimitrov. Dimitrov’s famous description of fascism was of it as “the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital” (1935). While there is more that can be said about this particular formulation of fascism, its pithy nature most certainly does have a certain political appeal to it. However it also clearly lacks the degree of specificity that one might consider necessary to make it actually helpful. Additionally, though this particular definition of fascism in many ways still is the definitive, go-to, definition amongst the revolutionary anti-capitalist movement, it is not the only one.

In particular I would note Don Hammerquist’s Fascism & Anti-Fascism. In this work Hammerquist, himself an autonomist Marxist, rejects the traditional, primarily Marxist-Leninist, Dimitrov derived view of fascism as simply a tool for big business. Indeed Hammequist states that:

In opposition to this position [NB: the Dimitrov position], I think that fascism has the potential to become a mass movement with a substantial and genuine element of revolutionary anti-capitalism. Nothing but mistakes will result from treating it as “bad” capitalism—as, in the language of the Comintern (2002: 10).

Centrally Hammerquist sees the danger in a new fascism that is more independent than the classical “euro-fascism” of the 1920s, 30s and 40s, and, seemingly in contradiction with broad left opinion, more oppositional to capitalism. For Hammerquist fascism is not some blunt instrument to be used used as a prop for industrial capitalism but is, rather, a whole new form of barbarism, one that quite disconcertingly comes with mass support. Perhaps most importantly Hammerquist emphasizes the degree to which fascism has its own independent political life, and as such, while it can be influenced by the bourgeoisie, it is ultimately independent of it. For him, fascism is a form of populist right-wing revolution (Hammerquist, 2002).

Agreeing with Hammerquist in broad strokes, while also putting forth criticisms and contributions, J. Sakai calls “disastrous” the old “1920s European belief that fascism was just ‘a tool of the ruling class’” (2002: 33). Sakai also emphasizes the class composition of fascist movements, using as his primary case study the German national socialist movement, noting them as primarily formed by men of lower middle class and declassed backgrounds (2002: 34). Sakai has also made interesting contributions to the role of ecological thought, in particular blood & soil doctrine, to fascist, in particular national socialist, thinking (2007).

However, while Hammerquist and Sakai’s writings on the question of fascism provide a most interesting, and probably fruitful, avenue for discussion, they nevertheless remain a minority view within the left. As such, let us return to Dimitrov’s definition which, as was noted above, remains the most popular by those self-professing credentials as part of the revolutionary anti-capitalist movement. It is here that I wish to direct my own critique of fascist ideology, identity, and the question of resistance.

Reflecting back on the lack of specificity within Dimitrov’s formulation of fascism, let us note that others have had to delve deeper into the fascist experience to flesh it out further and to attempt to deliver a genuinely helpful analytic. In particular, political economist Zak Cope (2015), in his book Divided World Divided Class: Global Political Economy and the Stratification of Labour Under Capitalism, sums up the attempts to give more depth to the Dimitrovian analysis of fascism, and it is worth quoting him at length. He says:

Fascism is the attempt by the imperialist bourgeoisie to solidify its rule on the basis of popular middle-class support for counter-revolutionary dictatorship. Ideologically fascism is the relative admixture of authoritarianism, racism, militarism and pseudo-socialism necessary to make this bid successful. In the first place, authoritarianism justifies right-wing dictatorship aimed at robbing and repressing any and all actual or potential opponents of imperialist rule. Secondly, racism or extreme national chauvinism provides fascist rule with a pseudo-democratic facade, promising to level all distinctions of rank and class via national aggrandisement. Thirdly, militarism allows the fascist movement both to recruit déclassé ex-military and paramilitary elements to its cause and to prepare the popular conscience for the inevitable aggressive war. Finally, social-fascism offers higher wages and living standards to the national workforce at the expense of foreign and colonised workers. As such, denunciations of “unproductive” and “usurers” capital, of “bourgeois” nations (that is, the dominant imperialist nations) and of the workers’ betrayal by reformist “socialism” are part and parcel of the fascist appeal (294).

As Cope further notes, this summation is not out of line with the pre-Dimitrov (and, also, pre-Hitlerian) discussion of fascism in the Programme of the Communist International, which noted that “[T]he combination of Social Democracy, corruption and active white terror, in conjunction with extreme imperialist aggression in the sphere of foreign politics, are the charecteristic features of Fascism” (1929). However, as with most of the contemporary left, Cope essentially remains within the general contours of Dimitrov’s work, holding fascism to be an “exceptional form of the bourgeois state” (2015: 294).

Beyond the COMINTERN: Colonial Violence Turned Inwards

For the colonized, both inside and outside of north amerika, these formulations of fascism are ultimately insufficient. However, in his own reading of fascism, Cope does open up a window onto what I propose is the true heart of fascism. He says: “Geographically speaking, on its own soil fascism is imperialist repression turned inward” (294). This is an aspect of fascism which I believe is essentially missing from other definitions, from the liberal-historical to Dimitrov, to Hammequist & Sakai, from both the pithy and the detailed. In essence, following this line of reasoning, we can say that fascism is when the violence that the colonialist-imperialist nations have visited upon the world over the course of the development of the modern, parasitic capitalist world-system comes back home to visit.

This direct lineal connection from colonial violence to fascism was beautifully, if disturbingly, described by Aimé Césaire in his Discourse on Colonialism (1972), saying:

[W]e must show that each time a head is cut off or an eye put out in Vietnam and in France they accept the fact…each time a Madagascan is tortured and in France and they accept the fact, civilization acquires another dead weight, a universal regression takes place, a gangrene sets in, a center of infection begins to spread; and that at the end of all these treaties that have been violated, all these lies that have been propagated, all these punitive expeditions that have been tolerated, all these prisoners who have been tied up and “interrogated, all these patriots who have been tortured, at the end of all the racial pride that has been encouraged, all the boastfulness that has been displayed, a poison has been instilled into the veins of Europe and, slowly but surely, the continent proceeds toward savagery (13).

Regarding the shock of fascism’s recapitulation of colonialist-imperialist violence arriving on the shores of the homeland Césaire adds:

People are surprised, they become indignant. They say: “How strange! But never mind-it’s Nazism, it will, pass!” And they wait, and they hope; and they hide the truth from themselves, that it is barbarism, but the supreme barbarism, the crowning barbarism that sums up all the daily barbarisms; that it is Nazism, yes, but that before they were its victims, they were its accomplices; that they tolerated that Nazism before it was inflicted on them, that they absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples; that they have cultivated that Nazism, that they are responsible for it, and that before engulfing the whole of Western, Christian civilization in its reddened waters, it oozes, seeps, and trickles from every crack (14).

So this brings me back to my secondary question, what does fascism mean to the Indigenous person? To the colonized? In particular, as Cope adds that fascism “whilst on foreign soil” is “imperialist repression employed by comprador autocracies” (2014: 294) or even Hammerquist and Sakai’s discussion of the globalization of fascism (2002; 2002)? But what does it mean for an analysis of fascism when being on “foreign soil” is also being in its “own soil?” In other words, what, if anything, can fascism mean to those of us trapped within the belly of a violent settler colonial beast?

The Terrain below Fascism

Building on this recognition of fascism as colonial violence turned inwards, we are then immediately confronted with the truth that the terrain for even the possibility of the development of a domestic fascist movement in north amerika is a terrain—in terms of both the literal material meaning of the land, as well as less direct meanings of the psychic, political, social, cultural, ideological and economic fields—is a terrain already soaked in blood. In particular it is a terrain that is already soaked in the blood of Red and Black Peoples.

In the case of the north amerikan settler colony, the sense of exteriority inherent in Césaire’s description of the perfection of what would become fascist oppression within the deployment of colonial violence overseas becomes interior. While for Césaire and Cope the violence of fascism is brought home from the distant colonies of the metropolitan imperialist powers, in the settler colonial context this violence is one that was perfected within the exceptional state of the expansion of the frontier, the clearing and civilizing of Indigenous People to make the land ripe for settlement, and the carceral continuum that has marked Black existence on this land from chattel slavery to the modern hyperghetto.

Thus, before one can even begin a discussion of fascism (or even capitalism for that matter[i]), and the possibility of its emergence on this land, it is important to recognize that fascism in north amerika can only occur in a context always-already defined by two fundamental axes of violence: indigenous genocide and antiblackness. These two axes, while being somewhat incommensurable with one another, also overlap, and of course also intersect with the general parasitism of the imperialist countries upon the Third World and other colonized peoples worldwide. Broadly we can say though that both the psychic and material life of white north amerikan society is sutured together by anti-indigenous and antiblack solidarity and violence.

Settler Colonialism & Indigenous Genocide

Firstly, north amerika is a settler colonial estate. As noted above, this means that one of the principal features that distinguishes north amerikan settler colonialism (as well as the autralasian and israeli forms) from more traditionally theorized metropolitan, or franchise, colonialism is the fundamental drive towards the elimination of Indigenous peoples (Veracini, 2010). This is what the late theorist of settler colonialism Patrick Wolfe referred to the logic of elimination (2006). Indeed for there to even be a kanada or a united states of amerika Indigenous People must disappear in order for non-Indigenous settlers to claim rightful ownership and title over the continent. Further the logic of elimination exists in a dialectic with an extensive project of settler self-indigenization. While this process is most stark in regions such as Appalachia and Quebec (Pearson, 2013) it is pervasive across the continent.

Additionally, while much of these processes have taken place juridically, and are daily reinforced within the codes of the civil society of the white settler nation, these processes are, and always have been, drenched in literal Native blood. To define Native life under the existence of settler colonialism is to see it defined through the multiple, converging “vectors of death” arrayed against us, and our resistance to them (Churchill, 2001). All of these processes can be summed up in what Nicolas Juarez refers to as the grammars of suffering of Red life: clearing and civilization (2014). Additionally, while this violence is structural and ontological, it is also enacted in a quotidian fashion by the settler population itself. As Patrick Wolfe notes, there is, from the Indigenous perspective, a fundamental inability to separate the individual settler from the settler state, with the former being the latter’s principal agent of expansion (2016).

Antiblackness and the Continued Inheritance of Enslaveability

Along with the clearing of the continent of Indigenous Peoples, within the racial discourses of north amerika, as thinkers as diverse as Sora Han (2002), Jared Sexton (2008) and Angela Harris (2000) have noted, blackness is equated with an inherent (and inheritable) status of enslaveability, and is marked for permanent exclusion from the social fold. While, as sociologist Loïc Wacquant has pointed out, the particular manifestations of this process have evolved over time—from chattel slavery, to Jim Crow, to the ghetto to the modern hyperghetto with its accompanying carceral continuum (the ghetto to prison to ghetto circuit)—the underlying logic has remained the same (2010; 2002). Under this regime the Black body itself becomes a site of accumulation, nothing more than property, which can then be subjected to violence. This is what Sexton, Frank B. Wilderson, III (2010) and other related theorists mean when they note that the grammars of suffering for Black life are accumulation and fungibility. The enduring legacy of antiblackness is the direct line from slaveability through lynching, extrajudicial executions of Black men, modern hyperincarceration and the criminalization of Blackness. All of this is enforced is enforced and made allowable by continuous, gratuitous antiblack violence.

What is Fascism then to Red and Black People?

So what then does fascism mean to us, the colonized, the Red and Black Peoples of this land, from whom it was stolen and who were stolen to work it? What does it mean for us if Trump is indeed a fascist? A proto-fascist? A para-fascist? What does it mean to us if he is one of those things, a right-wing national-populist, or something else entirely yet facilitates their rise and their existence?

To paraphrase the African People’s Socialist Party (2015) and Jesse Nevel of the Uhuru Solidarity Movement (2016), and to ask this question more specifically, what does the potential rise of fascism in north amerika mean to Red and Black peoples who have suffered, and who continue to suffer, the hells of genocide, slavery, land theft, convict leasing, forced marches, Jim Crow, popular lynchings, public police murders, corralling and containment in reservations, ghettos and barrios, mass incarceration numbering in the millions, residential schools, economic quarantine and military occupation of our communities? What does fascist violence mean to us as peoples who already face structural processes that seek to drive us to alcoholism, drug abuse, suicide, mental illness and abject poverty, and which, in collusion with the more blatant aspects of our colonial oppression, seek to wipe out Red and Black Bodies? What does fascist violence mean to us when we already live under such states identified by Jodi Byrd (2011) as “unlivable, ungrievable conditions within the state-sponsored economies of slow death and letting die” (38).

Thus it may seem that to equate our current status with fascism is erroneous, if not outright outrageous, given what our people have already experienced, and what we continue to experience on a daily basis. Again, the African People’s Socialist Party (2015) notes “A stand that fears Trump fails to recognize that when Africans in the U.S. were subjected to public, mass lynchings, that terror was carried out by non-fascist ‘democratic’ states and ordinary white citizens.”

However, with that said, we should not ignore the potential for violence in excess of standard settler colonial operating procedure that the modern north amerikan fascist movement holds. This is seen most starkly in the Quebec City mosque shootings. While the suspect, Alexandre Bissonnette, appears to have acted alone, we must not forget that this is a city where the local Soldiers of Odin chapter has stated that is wishes to launch patrols of Islamic neighbourhoods. In general we can say that, as noted by Stephen Pearson (2017), in excess of the right-wing national-populism of Trump and his kanadian interlocutors, these forces, whether they explicitly engage in the kind of German Nazi fetishism associated with such individuals and organizations Andrew Anglin of The Daily Stormer or the National Socialist Movement, something which many people continue to stereotype as the most publicly visible mark of fascism, they all thirst for a new frontier, for recolonization, for territories, for a white homeland. In other words, they thirst for the fulfilment of the settler dream—which is a project, it is important to note, they think has failed—to be dreamt anew

And this is where we can begin to tease out a distinction between a genuine fascist movement, and the right-wing national-populism of the Trump presidency. While Trump drove home the slogan “make America great again,” it was not fundamentally premised on the idea that the amerikan project had failed. The modern north amerikan fascist movement however embraces a body politic that embodies a love for what amerika “might have been, if only.” In this sense it is a different rhetoric and politic than that of Trump. Indeed, it exceeds the standard settler colonial project of settler self-Indigenization (though, of course, they engage in this as well) by way of a complete embrace of the settler self, including all its horrors. It is a proclamation of reassertion: white power naked and with no smiling lies. It is white power that is not only unashamed, but proud (Pearson, 2017)

Ultimately, however, the issue does fold back in on itself, because the fact of the foundational anti-indigenous and antiblack violence of the north amerikan political project is ever present. The basal liberalism of north amerikan political life and civil society has always articulated a war over life and death with two fundamental aims: the elimination of Indigenous peoples and the subjugation and exclusion of Black peoples. In this regard, liberalism and fascism in north amerika are on the same ethical-political continuum, one rooted in settler colonialism and antiblackness. In this regard, from the perspective of the colonized, the distance between a Dimitrovian formulation of fascism as a tool of big business and one rooted in Hammerquist and Sakai that regards it as an altogether different social force begins to lose its importance.

And so here we return again to the question of colonial violence in the politic of fascism, because from the perspective of colonized life, whether the governing political logic of the colonial state is liberal or fascist, the fundamental warfare remains in place. The principal threat then of fascism to colonized peoples is not one that we would move from a state of having not been subjected to violence from every angle to one where we would, but rather that the pacing of the eliminative and accumulative logics of settler colonialism would be accelerated.

However, this means that in the final analysis the question being posed to Red and Black peoples by our erstwhile white left allies, who right now are sounding the anti-fascist alarm, is an impossible choice between non-fascist, nominally “democratic” colonialism, and fascist colonialism. Not only is this an impossible choice, but it is also, as I have shown, a false one, because what is fascism in the face of gruelling colonial violence without end? At best the choice lies between a slow (“democratic”) and a fast (fascist) colonialism, in which the latter would most certainly accelerate north amerika’s underlying anti-indigenous and antiblack logics. We cannot choose between “democratic” colonialism and fascist colonialism because the ultimate problem is the same: colonialism.

What is to be Done?

All of that said though, the question remains of how do we fight fascism? For myself the answer is much the same as my answer to what we must do to fight capitalism (2016), and in this regard the answer is simple: anti-fascism without decolonization, genuine decolonization, is meaningless—if you want to fight fascism, you have to decolonize. Again, to quote the African People’s Socialist Party, ” Our liberation—and that’s what we must win—will only come about by an all-out struggle to overturn the colonial relationship we have with white power” (2015).

This is a basic truth that I believe should, indeed must, be grasped by all people claiming revolutionary credentials. We must have the power to decide our own fate, and we must be independent of any need to rely on the white ruling class, the colonialist-capitalist state and its institutions of civil society. Perhaps the most basic way to say this is to say that our goal must be Red and Black Power.

Additionally, as we move towards this goal, we must resist something that has become traditional for the white left when it comes to colonized peoples, which is to attempt to set the agenda for our liberation. A principal effect of this imperialist and opportunist practice on the part of the white left is to disorient our peoples, turn us away from the struggle against the forces and structures of colonialization, and to set as the common programme for all the needs of the colonizer, over and above the needs of the colonized (African People’s Socialist Party, 2015; Ena͞emaehkiw Wākecānāpaew Kesīqnaeh, 2016).

But what does Decolonization look like? What does Red and Black Power look like? The overarching goal of course is, as the African People’s Socialist Party States, “the revolutionary overthrow of U.S. capitalist-colonialism—this includes U.S. capitalist-colonialist democracy or fascism or whatever form the colonial State assumes in imposing its illegitimate rule over our oppressed people” (2015). In particular though the programme of decolonization was broken down into three succinct aspects by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012), outlined below with a few expansions of my own:

- The repatriation of land to sovereign Native nations; that is, all of the land, not just symbolically and without compensation for the settler population who stole it and who’s continued occupation has been to ensure that it remains stolen;

- The abolition of slavery in its contemporary forms, including the carceral continuum of antiblackness, reparations to Afrikan people for kidnapping and stolen labour and the right to control their own communities free of military occupation;

- The dismantling of the imperialist metropole, and an end to the parasitism of the imperialist nations upon the bodies of the colonized peoples of the Third World.

These goals are also summed up in part by Frank B. Wilderson, III who asks, and then answers:

What are the foundational questions of the ethico-political? Why are these questions so scandalous that they are rarely posed politically, intellectually, and cinematically—unless they are posed obliquely and unconsciously, as if by accident? Give Turtle Island back to the “Savage.” Give life itself back to the Slave. Two Simple sentences, fourteen simple words, and the structure of U.S. (and perhaps global) antagonisms would be dismantled (2010: 2-3)

To put it another way, and to echo the great revolutionary anti-colonial leader of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Amílcar Cabral (1972), while we cannot be sure that the defeat of fascism (or capitalism) alone will be enough to bring about the decolonization of Turtle Island, we can be sure that the defeat of colonialism on this land will be the final defeat of even the possibility of fascism, much less fascism itself.

Finally, all of this applies to white people as well, many of whom I know are worried, as I said before, about the possibile rise of fascism in the united states and kanada. I say to you, my white friends, coworkers and allies, that the best way for you to guarantee the defeat of fascism is to rise with us, in solidarity with us, and united with our goals for decolonization. Join us in fighting against the parasitic relationship all white people have enjoyed at our expense for 600 years. Work in solidarity to Defeat u.s., kanadian and european colonialism–in all corners of the world, from Afrika, to the Caribbean, to Afghanistan, to Palestine, to Syria, to the South China Sea, to so-called “South America” to Turtle Island–and fascism, along with all the other most vile manifestations of capitalism, will surely fall with it.

A better world awaits all of us.

Notes

[i] To be clear, as I have always tried to be on this site, I am not saying that capitalism is not problem. It most certainly is, and I believe for there to ever be any kind of development of real world wide justice then the capitalist world-system must be torn down and replaced. In this regard, despite ideological growth I retain many of my old Marxist principles, commitments and points of analysis.

[ii] While I hear quote Smith, it is not an endorsement of her, especially in light of the question that have arisen in the past few years regarding the veracity of her claims to Indigeneity.

References

African People’s Socialist Party. 2015. “Colonialism Trumps Fascism in U.S. Elections.” The Burning Spear, September 8.

Byrd, Jodi A. 2011. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Cabral, Amílcar. 1974. “In Guinea and Cabo Verde against Portuguese Colonialism.” In Revolution in Guinea: Selected Texts, 10-19. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

Césaire, Aimé. 1972. Discourse on Colonialism. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

Churchill, Ward. 2001. A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books.

COMINTERN. 1929. The Programme of the Communist International Together with the Statutes of the Communist International. London, UK: Modern Books.

Cope, Zak. 2015. Divided World Divided Class: Global Political Economy and the Stratification of Labour Under Capitalism.. Montreal, QC Kersplebedeb.

Dimitrov, Georgi. 1935. “Against Fascism & War.” Report to the 7th World Congress of the Communist International.

Griffin, Roger, and Matthew Feldman. 2004. Fascism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. London, UK: Routledge.

Hammerquist, Don. 2002. “Fascism & Anti-Fascism.” In Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement, 10-32. Montreal, QC: Kersplebedeb.

Han, Sora. 2002. “Veiled Threars.” American Studies Association Annual Meeting.

Harris, Angela P. 2000. “Embracing the Tar-Baby: Latcrit Theory and the Stick Mess of Race.” In Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge, edited by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, 440-447. Philadelphia, PN: Temple University Press.

Juarez, Nicolas. 2014. “To Kill an Indian to Save a (Hu)Man: Native Life .” Wreck Park 1.

Kesīqnaeh, Ena͞emaehkiw Wākecānāpaew. 2016. “The ABCs of Decolonization.” Maehkōn Ahpēhtesewen, May 16.

Nevel, Jesse. 2016. “Trump and Clinton: Both Representatives of White Power.” The Burning Spear, November 15.

Pearson, Stephen. 2013. “‘The Last Bastion of Colonialism’: Appalachian Settler Colonialism and Self-Indigenization.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 37 (2): 165-184.

—. forthcoming. “‘Enter the Amerikaner Free State’: The Alt Right and Settler Colonialism.” Journal of Labor and Society.

Sakai, J. 2002. “The Shock of Recognition: Looking at Hammerquist’s Fascism & Anti-Fascism.” In Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement, 33-68. Montreal, QC: Kersplebedeb.

—.2007. The Green Nazi: An Investigation into Fascist Ecology. Montreal, QC: Kersplebedeb.

Sexton, Jared. 2008. Amalgamation Schemes: Antiblackness and the Critique of Multiracialism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Smith, Andrea. 2010. “Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy.” In Racial Formation in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Daniel Martinez HoSang, Oneka LaBennett and Laura Pulido, 66-90. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization is not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1-40.

Veracini, Lorenzo. 2010. Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2002. “Deadly Symbiosis: When Ghetto and Prison Meet and Mesh.” Punishment and Society 3 (1): 95-133.

—. 2010. “Class, Race and Hyperincarceration in Revanchist America.” Daedalus 139 (3): 74-90.

Wilderson III, Frank B. 2010. Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387-409.

—. 2016. Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race. London, UK: Verso.

#policestate

Do “We keep us safe”? Notes on Action Security & Some Resources

Published

2 years agoon

September 30, 2023By

Rudy

“We keep us safe!” is an abolitionist assertion that the state or some paternalistic organization will not protect us from colonial, fascist, white supremacist, queerphobic attacks, so we must organize and defend ourselves and those we are in community with.

We cannot leave this slogan to be an empty gesture or posture. It must be conveyed with the necessary training and organizing to address the hyperpoliticized and conflictual environments that we organize in.

While we cannot anticipate and prevent all fascist assaults, if we pronounce that “we keep us safe,” we can and must do what we can to organize and be prepared. Liberal and “radical” non-profit managers constantly decrying the “inactions of cops” does not keep us safe, it only invokes further police violence. Additionally, calling on colonial politicians to respond to fascist violence as a “hate crime,” is really a call to further the carceral state and its institutional violences (courts, prisons, more policing, etc).

On September 28th, 2023 Jacob Johns, an Indigenous persn was shot by Ryan Martinez, a colonial invader and MAGA fascist at an action called to confront the re-establishment of a monument to the genocidal colonizer Juan de Oñate in so-called Española, New Mexico. This shooting occurred under the same watch of an organization that hosted a previous anti-Oñate monument action in 2020 where Scott Williams was shot and severely injured.

From Heather Heyer, Joseph Rosenbaum, and Anthony Huber to many more who have been injured or killed while resisting authoritarian nationalism (aka fascism), these deadly attacks are occurring within a context of historic, ongoing, and escalating colonial violence.

Since 2020, groups based in occupied New Mexico organizing anti-monument actions have been directly challenged for putting people at serious risk. Calls that have been made for more organized security have been denounced by inexperienced organizers in these groups.

These issues and considerations are not new, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense and AIM initiated armed patrols and armed resistance in the face of state, white supremacist, and colonial terror. Amorphous entities such as Antifa and Bash Back have continually mobilized street warfare in defensive and proactive ways. These groups have long recognized that we cannot merely rely on “safety in numbers,” (though numbers do help) our enemies are more organized than that, so why aren’t we?

We cannot pronounce liberation without simultaneously preparing and mobilizing defense.

As everyone should be doing mutual aid, everyone should be prepared for mutual defense. We cannot depend on any organizers or organizations to simply do this for us. If “We keep us safe,” we better fucking mean it.

As Goldfinch Gun Club stated, “Community defense has to be about solidarity and uplift mutual aid, not just arming vulnerable peoples. By the time someone starts shooting, everyone has already lost. The best defense is a better world. It’s possible. We have to believe that.”

Support Jacob Johns, his family and community by contributing to the gofundme: https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-jacob-johns-recover-from-terrorist-shooting?utm_campaign=p_cp+share-sheet&utm_medium=copy_link_all&utm_source=customer

Some recommendations:

1. Organize and attend street medic trainings. Check these resources:

A Demonstrator’s Guide to Responding to Gunshot Wounds https://crimethinc.com/2020/09/24/a-demonstrators-guide-to-responding-to-gunshot-wounds-what-everyone-should-know

An Activist’s Guide to Basic First Aid https://www.sproutdistro.com/catalog/zines/direct-action/activists-guide-to-basic-first-aid/

2. Organize armed self defense. Check these resources:

Three Way Fight: Revolutionary Anti-Fascism and Armed-Self-Defense https://itsgoingdown.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/three_way_fight_print.pdf

Organizing Armed Defense in “America”

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/organizing-armed-defense-in-america

Gun Clubs:

https://www.hueypnewtongunclub.org/survival-programs

https://www.pinkpistols.org/about-the-pink-pistols/

https://socialistra.org/

https://www.john-brown-gun-club.org/about (Note: their founder and a lead organizer of Red Neck Revolt/JBGC is a known abuser).

3. Develop and maintain clear security protocols and presence (if not visible at least organized).

A note: By security we don’t mean leftist police, we mean skilled warriors who are identified to respond and protect, not police actions. Beware of cis-heteropatriarcal and other oppressive behaviors, substance use, & abusers, etc.

Being prepared can be an escalation in and of itself, it also can be a powerful deterrent. Do what makes sense for your operating environment.

Defend Pride

https://www.sproutdistro.com/catalog/zines/direct-action/defend-pride/

Forming an Antifa group

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/forming-an-antifa-group

Check out all these great resources on Security Culture:

https://www.sproutdistro.com/catalog/zines/security/

These ‘zines particularly address cop tactics but have great info for overall security:

Defend the Territory

https://www.sproutdistro.com/catalog/zines/direct-action/defend-the-territory

Warrior Crowd Control & Riot Manual

https://www.sproutdistro.com/catalog/zines/direct-action/warrior-crowd-control-riot-manual/

Other resources:

Dangerous Spaces: Violent Resistance, Self-Defense, and Insurrectional Struggle Against Gender

https://archive.org/details/dangerous-space-EN-pageparpage/mode/2up

Repress This

https://itsgoingdown.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/imposed-repress_this_print.pdf

#nonukes

A quick & dirty review of the movie Oppenheimer

Published

3 years agoon

July 20, 2023By

Rudy

We watched this movie after arguing with social media pro-nuke apologists who accused us of being ill-informed as not having viewed Christopher Nolan’s biopic, so excuse the mess… (and if you haven’t already, read our initial post here for the context).

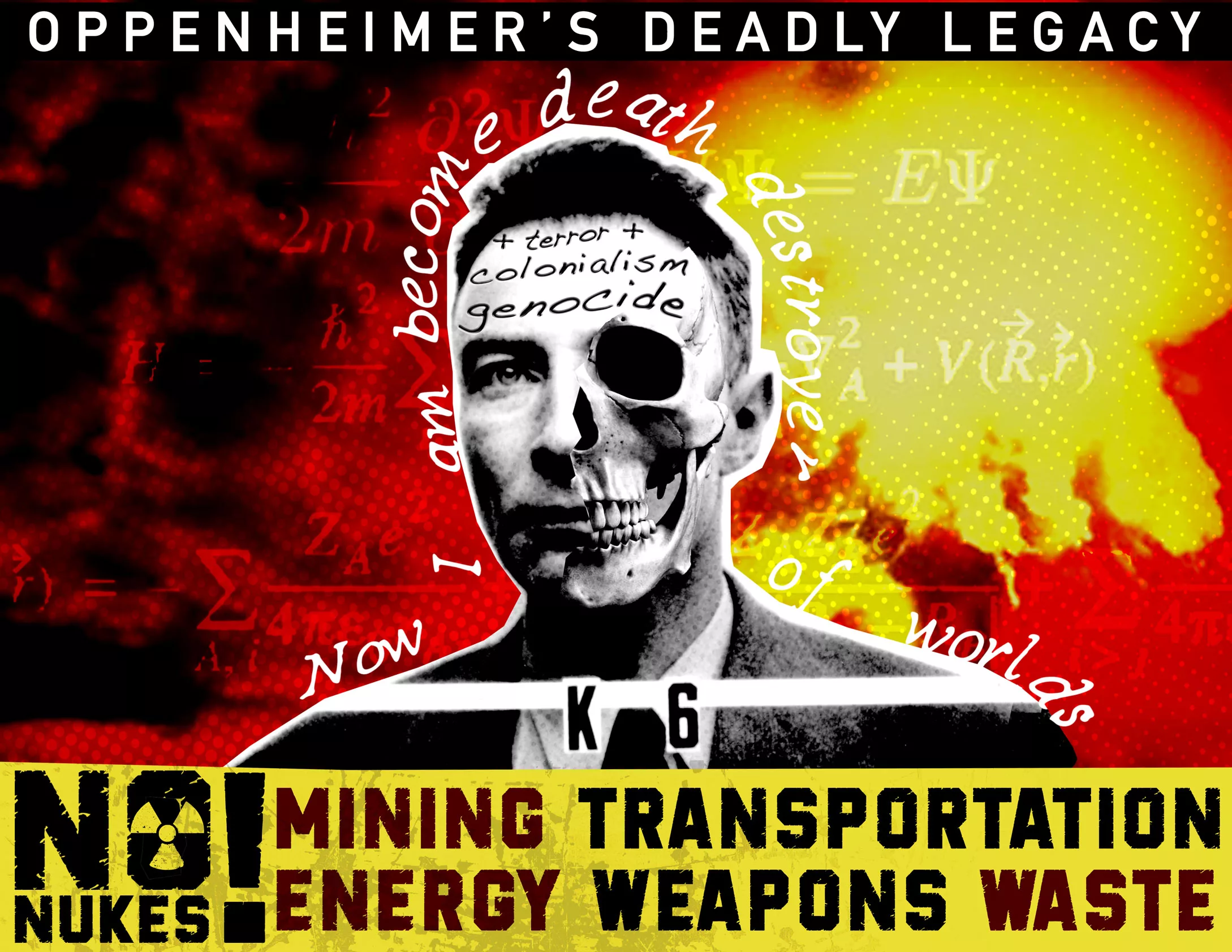

Oppenheimer is a glorification of the “complicated genius” and ambitions of white men making terrible decisions that imperil the world.

Many have remarked that the film is not a glorification, yet Christopher Nolan himself says, “Like it or not, J Robert Oppenheimer is the most important person who ever lived.”

Some of you may have even had a burst of laughter during the scene where Truman asked Oppenheimer what he thought the fate of Los Alamos should be and “Oppie” retorted, “Give the land back to the Indians.” But alas, the poisoned scarred landscape today is host to a 10-day “Oppenheimer Festival.” To underscore the disconnect of legacies, a small commemoration near the Churchrock spill site was also held on the anniversary of the Trinity detonation, a few hundred miles away. Yes, what glorification?

The movie is basically a Western à la John Wayne. It very well could have been called, “The Trial of the Sheriff of Los Alamos.”

Oppenheimer rides his horse with a black hat on and pulls a poster down from a fence post. He then strides into a debate on the “Impact of the gadget on civilization.” To respond to the question of how scientists can justify using the Atom Bomb on human beings, Oppenheimer speaks, “We’re theorists yes, we imagine a future and our imaginings horrify us. They won’t fear it until they understand it and they won’t understand it until they’ve used it. When the world learns the terrible secret of Los Alamos our work here will ensure a peace mankind has never seen. A peace based on international cooperation.”

Nolan establishes the only narrative that matters is his attempt at historical redemption, he paints Oppenheimer as a victim. While perhaps not as depoliticized as Nolan alluded to in interviews (as the politics of American loyalty and the Red Scare drive the drama), the consequences of nuclear weapons and energy is barely considered (arguably barely at all considering the issue). This is a political omission of the most insidious sort and the film is even worse for it.

The movie cares more about constructing and clearing Oppenheimer as a victim of McCarthyism than the impacts of the atomic bomb and its deadly legacy of nuclear colonialism. As it’s stated, there’s a “Price to be paid for genius.” Everything else is dramatic notation. Nolan gives Oppenheimer the public hearing he feels like he was denied to ultimately prove he was an American patriot. In the end, the question “Would the world forgive you if you let them crucify you?” matters above all other concerns. The movie poses the argument as “science versus militarism” while the world and Indigenous Peoples continue to suffer the permanent consequences of nuclear weapons and energy in silence. A deadly silence more deafening than Nolan’s cinematic portrayal of the Trinity test. But hey, there’s even a minute of cheering after the test.

Nolan has us listening to the radio while two cities are destroyed and hundreds of thousands of lives are taken. Nolan keeps the camera on his lead actor’s face while the horrors of his bomb are shown on slides. Oppenheimer simply looks away. What more about this film do we need to know?

15,000 abandoned uranium mines poisoning our bodies, lands, and water. 1,000 bombs detonated on Western Shoshone lands… the list goes on (we only stop here because we’ve stated much more in our original post). All omitted and sentenced to suffer in catastrophic silence. Films like Oppenheimer are only possible because people keep looking away from the deadly reality of nuclear weapons and energy.

#nonukes

Architect of Annihilation: Oppenheimer’s Deadly Legacy of Nuclear Terror

Published

3 years agoon

July 20, 2023By

Rudy

Read our quick and dirty review of the movie here.

Klee Benally, Indigenous Action/Haul No!

Contributions by Leona Morgan, Diné No Nukes/Haul No!

Printable posters (PDFs): 11″x17″ color, 11″x17″ black & white

The genocidal colonial terror of nuclear energy and weapons is not entertainment.

To glorify such deadly science and technology as a dramatic character study, is to spit in the face of hundreds of thousands of corpses and survivors scattered throughout the history of the so-called Atomic age.

Think of it this way, for every minute that passes during the film’s 3-hour run time, more than 1,100 citizens in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki died due to Oppenheimer’s weapon of mass destruction. This doesn’t account for those downwind of nuclear tests who were exposed to radioactive fallout (some are protesting screenings), it doesn’t account for those poisoned by uranium mines, it doesn’t account for those killed during nuclear power plant melt-downs, it doesn’t account for those in the Marshall Islands who are forever poisoned.

For every second you sit in the air conditioned theater with a warm buttery popcorn bucket in your lap, 18 people dead in the blink of an eye. Thanks to Oppenheimer.

Though you’ll certainly learn enough about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” thanks to director Christopher Nolan’s 70mm IMAX odyssey, let’s be clear about his deadly legacy and the overall military and scientific industrial complex behind it.

After the successful detonation of the very first atomic bomb, Oppenheimer infamously quoted the Hindu scripture Bhagavad-Gita, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” Barely a month later, the “U.S” dropped two atomic bombs devastating the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and more than 200,000 people were killed. Some of the shadows of those perished were burned into the streets. One survivor, Sachiko Matsuo, relayed their thoughts as they tried to make sense of what was happening when Nagasaki was struck, “I could see nothing below. My grandmother started to cry, ‘Everybody is dead. This is the end of the world.” A devastation that Nolan intentionally leaves out because, according to the director, the film is not told from the perspectives of those who were bombed, but by those who were responsible for it. Nolan casually explains, “[Oppenheimer] learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio, the same as the rest of the world.”

Months after the atomic detonation at the “Trinity” site in occupied Tewa lands of New Mexico, Oppenheimer resigned. He walked away expressing the conflict of having, “blood on his hands,” (though reportedly he later said the bombings were not “on his conscience”) while leaving a legacy of nuclear devastation and radioactive pollution permanently poisoning lands, waters, and bodies to this day.

U.S. military and political machinery cannibalized the scientist and turned him into a villain of their imperialist cold-war anxiety. They reminded him and the other scientists behind the Manhattan Project, that they and their interests were always in control.

Oppenheimer never was a hero, he was an architect of annihilation.

The race to develop the first atomic bomb (after Nazis had split the atom) never could be a strategy of peaceful deterrence, it was a strategy of domination and annihilation.

Nazi Germany was committing genocide against Jewish people while the U.S. sat on the political sidelines. It wasn’t until they were directly threatened that the U.S. intervened. Though Nazi Germany was defeated on May 8th, 1945, the U.S. dropped two separate atomic bombs on the non-military targets of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th, 1945.

To underscore Oppenheimer’s complicity, he suppressed a petition by 70 Manhattan Project scientists urging President Truman not to drop the bombs on moral grounds. The scientists also argued that since the war was nearing its end, Japan should be given the opportunity to surrender.

Today there are approximately 12,500 nuclear warheads in nine countries with almost 90 percent of them held by the U.S. and Russia. It is estimated that 100 nuclear weapons is an “adequate… deterrence” threshold for the “mutually assured destruction” of the world.

Oppenheimer built the gun that is still held to the head of everyone who lives on this Earth today. Throughout the decades after the development of “The Bomb,” millions throughout the world have rallied for nuclear disarmament, yet politicians have never taken their fingers off the trigger.

The Deadly Legacy of Nuclear Colonialism

Nuclear weapons production and energy would not be possible without uranium.

Global uranium mining boomed during and after World War II and continues to threaten communities throughout the world.

Today, more than 15,000 abandoned uranium mines are located within the so-called U.S., mostly in and around Indigenous communities, permanently poisoning sacred lands and waters with little to no political action being taken to clean up their deadly toxic legacy.

Indigenous communities have long been at the front lines of the struggle to stop the deadly legacy of the nuclear industry. Nuclear colonialism has resulted in radioactive pollution that has poisoned drinking water systems of entire communities like Red Shirt Village in South Dakota and Sanders in Arizona. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has closed more than 22 wells on the Navajo Nation where there are more than 523 abandoned uranium mines. In Ludlow, South Dakota an abandoned uranium mine sits within feet of an elementary school, poisoning the ground where children continue to play to this day.

Nuclear colonialism has ravaged our communities and left a deadly legacy of cancers, birth defects, and other serious health consequences, it is the slow genocide of Indigenous Peoples.

From 1944 to 1986 some 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted from mines on Diné lands. Diné workers were told little of the potential health risks with many not given any protective gear. As demand for uranium decreased the mines closed, leaving over a thousand contaminated sites. To this day none have been completely cleaned up.

On July 16, 1979, just 34 years after Oppenheimer oversaw the July 16, 1945 Trinity test, the single largest accidental release of radioactivity occurred on Diné Bikéyah (The Navajo Nation) at the Church Rock uranium mill. More than 1,100 tons of solid radioactive mill waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive tailings poured into the Puerco River when an earthen dam broke. Today, water in the downstream community of Sanders, Arizona is poisoned with radioactive contamination from the spill.

Although uranium mining is now banned on the reservation due to advocacy from Diné anti-nuclear organizers, Navajo politicians have sought to allow new mining in areas already contaminated by the industry’s toxic legacy. It is estimated that 25% of all the recoverable uranium remaining in the country is located on Diné Bikéyah.

Though there has never been a comprehensive human health study on the impacts of uranium mining in the area, a focused study has detected uranium in the urine of babies born to Diné women exposed to uranium.

Western Shoshone lands in so-called Nevada, which have never been ceded to the “U.S.” government, have long been under attack by the military and nuclear industries.

Between 1951 and 1992 more than 1,000 nuclear bombs have been detonated above and below the surface at an area called the Nevada Test Site on Western Shoshone lands which make it one of the most bombed nations on earth. Communities in areas around the test site faced severe exposure to radioactive fallout, which caused cancers, leukemia & other illnesses. Those who have suffered this radioactive pollution are collectively known as “Downwinders.”

Western Shoshone spiritual practitioner Corbin Harney, who passed on in 2007, helped initiate a grassroots effort to shutdown the test site and abolish nuclear weapons. He once said, “We’re not helping Mother Earth at all. The roots, the berries, the animals, are not here anymore, nothing’s here. It’s sad. We’re selling the air, the water, we’re already selling each other. Somewhere it’s going to come to an end.”

Between 1945 and 1958, sixty-seven atomic bombs were detonated in tests conducted in Ṃajeḷ (the Marshall Islands). Some Indigenous people of the islands have all together stopped reproducing due to the severity of cancer and birth defects they have faced due to radioactive pollution.

In 1987 the “U.S.” congress initiated a controversial project to transport and store almost all of the U.S.’s toxic waste at Yucca Mountain located about 100 miles northwest of so-called Las Vegas, Nevada. Yucca Mountain has been held holy to the Paiute and Western Shoshone Nations since time immemorial. In January 2010 the Obama administration approved a $54 billion dollar taxpayer loan in a guarantee program for new nuclear reactor construction, three times what Bush previously promised in 2005.

There are currently 93 operating nuclear reactors in the so-called U.S. that supply 20% of the country’s electricity. There are nearly 90,000 tons of highly radioactive spent nuclear waste stored in concrete dams at nuclear power plants throughout the country with the waste increasing at a rate of 2,000 tons per year.

From the 1979 disasters of Three Mile Island and Churchrock to the 1986 Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant melted down, the nuclear industry has been wrought with mass catastrophes with permanent global consequences.

In 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant catastrophically failed and began melting down after it was hit by an earthquake and tsunami. It’s been reported that the Fukushima plant has been leaking approximately 300 tons of radioactive water into the ocean every day. Today, the Japanese government is open about its plans to release remaining radioactive waters into the Pacific.

“Depleted Uranium” weapons deployed by the U.S. in imperialist wars (particularly Iraq and Afghanistan) have also poisoned eco-systems, including at proving grounds and firing ranges in Arizona, Maryland, Indiana and Vieques, Puerto Rico. Depleted uranium is a by-product of uranium enrichment process when it’s used for nuclear reactor fuel and in the making of nuclear weapons.

Nuclear energy production is now claimed as a “green solution” to the climate crisis, but nothing could be further from the truth of this deadly lie.

In April 2022, the Biden administration announced a $6 billion government bailout to “rescue” nuclear power plants at risk of closing. A colonial government representative stated, “U.S. nuclear power plants contribute more than half of our carbon-free electricity, and President Biden is committed to keeping these plants active to reach our clean energy goals.” They, along with Climate Justice activists cite nuclear energy as necessary to combat global warming, all while ignoring the devastating permanent impacts Indigenous Peoples have faced.

Due to this “greenwashing” of nuclear energy, we face a push for nuclear hydrogen, small modular nuclear reactors, and High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) driving a renewed threat of new uranium mining, transportation, & processing.

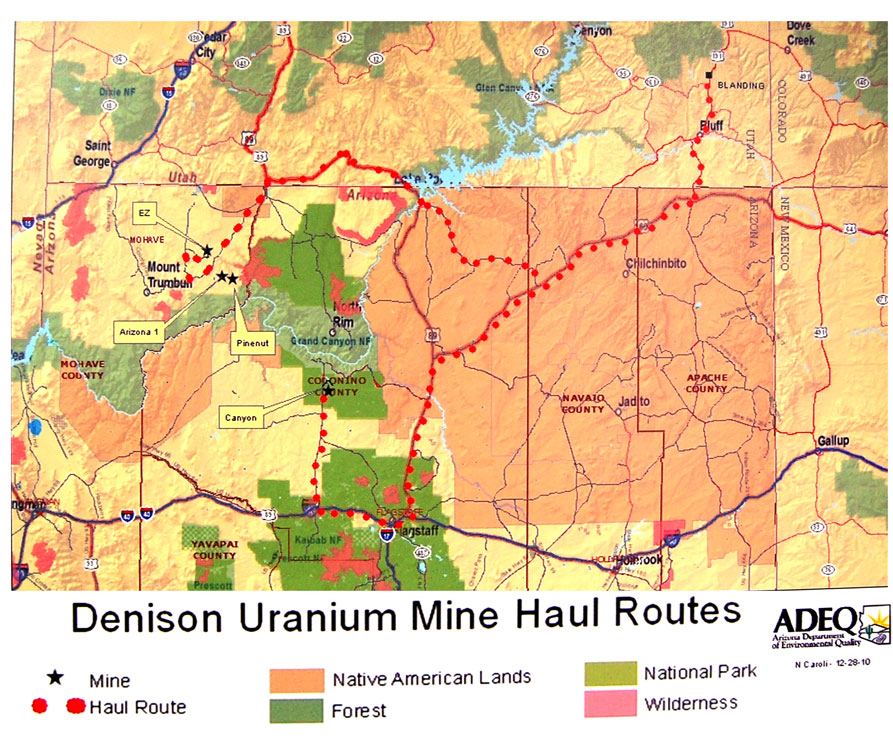

Though the Obama administration placed a moratorium on thousands of uranium mine leases around the Grand Canyon in 2012, pre-existing uranium claims were allowed. Environmental groups and Indigenous Nations are currently attempting to make the moratorium permanent and push for a new national monument, yet these will do little to nothing for the handful of pre-existing uranium mines that have been allowed to move forward.

Despite these actions, underground blasting & above ground work has begun at Pinyon Plain/Canyon Mine, just miles from the Grand Canyon. Once Energy Fuels, the company operating the mine, starts hauling out radioactive ore, they plan to transport 30 tons per day through Northern Arizona to the company’s processing mill in White Mesa, 300 miles away.

The White Mesa Mill is the only conventional uranium mill licensed to operate in the U.S. The mill was built on sacred ancestral lands of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe near Blanding, Utah. Energy Fuels disposes radioactive and toxic waste tailings in “impoundments” that take up about 275 acres next to the mill. Since there are limited radioactive waste facilities, White Mesa Mill has become an ad hoc dump for the world’s nuclear wastes that have no final repository.

In so-called New Mexico, a state addicted to nuclear monies for both nuclear weapons and energy facilities, there are two national nuclear labs and two national waste facilities. Along with legacy uranium mines and mills, there was Project Gasbuggy (an underground detonation), a “Broken Arrow” accident near Albuquerque, and countless tons of radioactive waste buried in unlined pits, Pueblo kivas, and watersheds. Currently, there are planned expansions and modifications at Los Alamos National Labs, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, and Urenco uranium enrichment facility. Most recently, the state has been threatened by two newly licensed consolidated interim storage facilities for “spent fuel” from nuclear power plants in New Mexico and Texas. The federal government continues to push nuclear projects with financial incentives.

Nuclear proliferation continues as the U.S. allows uranium miners and others who are eligible for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to die. Many continue to suffer and wait for compensation funds to be allocated or are not eligible due to the limitations of the act.

The devastation of nuclear colonialism, which permanently destroys Indigenous communities throughout the world, is not entertainment. This is the terrifying legacy of nuclear energy and weapons that movies like Oppenheimer and duplicitous climate justice activists advocate.

Indigenous Peoples live, suffer, and continue to resist its consequences every day.

END NUCLEAR COLONIALISM!

###

Recommended links:

https://haulno.com

http://www.dinenonukes.org

https://tewawomenunited.org/programs/environmental-health-and-justice-program

https://stopforeverwipp.org/home

https://www.trinitydownwinders.com/

http://www.cleanupthemines.org

https://www.nirs.org/

https://www.radioactivewastecoalition.org

https://www.dont-nuke-the-climate.org/

https://www.nuclear-heritage.net/index.php?title=Nuclear_Heritage_Network

https://yukiyokawano.com

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBO_C6GkIpM&t=10s

https://apjjf.org/2022/1/Schattschneider-Auslander.html

Articles:

Red Water Pond Road

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/a-radioactive-legacy-haunts-this-navajo-village-which-fears-a-fractured-future/2020/01/18/84c6066e-37e0-11ea-9541-9107303481a4_story.html

ABQ Museum

https://www.abqjournal.com/lifestyle/arts/albuquerque-museums-online-exhibit-trinity-takes-a-look-at-the-aftermath-of-the-atomic-bomb/article_33d17c15-61c8-5e1f-b32c-99f4ebee5db4.html

Get updates via email, sign up here:

Indigenous Action Podcast

- Indigenous Action Podcast Ep. 18: No Settler Future An Anti-Year in Review (sorta)

- Indigenous Action Podcast Episode 17: Decolonization isn’t a Holiday

- Indigenous Action Podcast Episode 16: Fuck a Valentine, Indigenous Abolition Feminism

- Indigenous Action Podcast Episode 15: 15th Annual No Thanks, No Giving: Indigenous Anarchism

- Indigenous Action Podcast Episode 14: Queering #MMIWG2ST

Popular Posts

-

Commentary & Essays12 years ago

Commentary & Essays12 years agoAccomplices Not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex

-

anti-colonial6 years ago

anti-colonial6 years agoVoting is Not Harm Reduction – An Indigenous Perspective

-

anti-colonial6 years ago

anti-colonial6 years agoRethinking the Apocalypse: An Indigenous Anti-Futurist Manifesto

-

Feature Front2 years ago

Feature Front2 years agoThe family of Klee Benally thanks you for the donations!

-

#nonukes12 years ago

#nonukes12 years agoIndigenous Elders and Medicine Peoples Council Statement on Fukushima

-

anti-colonial4 years ago

anti-colonial4 years agoUnknowable: Against an Indigenous Anarchist Theory – Zine

-

#nonukes16 years ago

#nonukes16 years agoUranium Mining Begins Near Grand Canyon

-

#policestate5 years ago

#policestate5 years ago16 Things You Can Do To Be Ungovernable. P.S. Fuck Biden